OKAVANGO WILDERNESS PROJECT

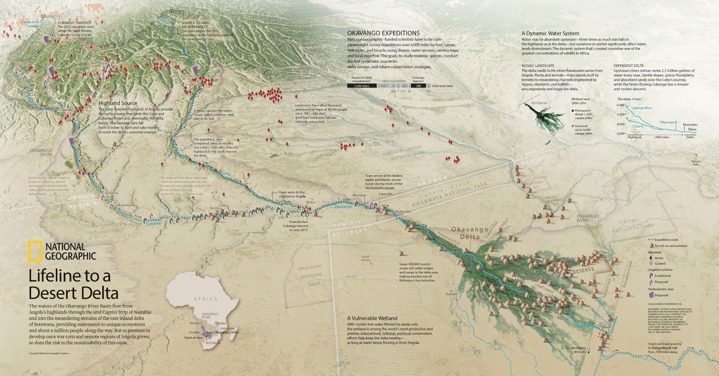

The Cuito, Cubango and Cuanavale Rivers in south east Angola are the life blood of the Okavango River Basin, converging then flowing through Namibia and into Botswana. The basin is one of the most beautiful but fragile eco systems in the world and the main source of water for more than one million people. But its future is uncertain. The vital headwaters in Angola remain unprotected, vulnerable to unwise development.

(Photograph: Kyle Gordon | National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project | www.natgeo.org/okavango)

The Angolans call this part of their country the land at the end of the earth, where the wind turns. However, beneath the pristine wilderness lurk tens of thousands of deadly landmines.

The Angolans call this part of their country the land at the end of the earth, where the wind turns. However, beneath the pristine wilderness lurk tens of thousands of deadly landmines, laid during the country’s brutal 27-year civil war. This is the most mined region in Angola, encompassing the provinces of Cuando Cubango, Moxico and Bié.

Since 1994, HALO has been working to remove this lethal threat, destroying over 95,000 landmines across the entire country, allowing devastated communities to rebuild after years of conflict. In 2015, National Geographic launched the Okavango Wilderness Project, recognising the urgent need to protect the river basin for future generations. But to reach the vital headwaters of the Okavango meant crossing through south east Angola. HALO was able to step in, providing safe passage and logistical support through hundreds of miles of remote bush, opening up the region to scientific exploration for the very first time.

(Photograph: Flavio Cardoso | National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project | www.natgeo.org/okavango)

Since 1994, HALO has destroyed over 95,000 landmines across Angola, allowing devastated communities to rebuild after years of conflict.

Season by season, the National Geographic team have returned to the source of the Okavango, supported by HALO every step of the way. They are documenting vital data, information needed to develop plans to protect this precious wilderness.

(Photograph: Chris Boyes | National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project | www.natgeo.org/okavango)

“We have made some incredible discoveries, including 30 new species to science. None of this would have been possible without the help of The HALO Trust.”

(Steve Boyes, National Geographic.)

The National Geographic team is using their scientific and survey work to build connections among governments, non-governmental organizations, and local communities to help establish the sustainable management of the Okavango’s source rivers in Angola. HALO’s work, clearing the landmines of Cuando Cubango, Moxico and Bié, is fundamental to achieving this vision.

(Photograph: James Kydd | National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project | www.natgeo.org/okavango)

HALO’s work, clearing the landmines of Cuando Cubango, Moxico and Bié, is fundamental to the vision for the sustainable management of the Okavango River Basin.

(Photograph: Kostadin Luchanski | National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project | www.natgeo.org/okavango)